First Women Enlist In The Marines

On August 13, 1918, Opha Mae Johnson became the first woman to enlist in the US Marine Corps Reserve.

According to legend, the first American female Marine may have been Lucy Brewer. Stories claim she disguised herself as a man and snuck aboard the USS Constitution during the War of 1812. However, there is little evidence to support that claim.

When the US entered World War I in April 1917, thousands of young men volunteered to fight for their country, while many more became drafted into service. With thousands of men leaving the country to fight, this left open positions that some realized could be filled by women. In May 1917, the Navy began admitting women to serve in administrative positions. Months later, the Secretary of the Navy remarked, “In my opinion, the importance of the part which our American women play in the successful prosecution of the war cannot be overestimated.”

Soon, new organizations such as the National League for Women’s Services and the Women’s Committee of the Council of National Defense were formed to help organize women’s activities all over the country. Much of this included volunteer work – making bandages, knitting clothes, planting victory gardens, and canning food. Women also began organizing book and clothing drives and selling Liberty Bonds. They also began taking over jobs that were traditionally held by men – elevator operators, streetcar conductors, postal carriers, and industrial workers.

As American involvement in the war continued, the need for additional workers hit the military especially hard. The Army sought to include women, but the law at the time specifically only permitted the enlistment of men.

By July 1918, war demands reached an all-time high. In the Marines, there was a shortage of trained personnel and men were sent to Europe as soon as possible. Then it was discovered that there was a large number of battle-ready Marines doing clerical work in the US, despite being badly needed at the front. The Marines then investigated the possibility of employing women for these clerical jobs. On August 2, the Marines requested authority to hire women for clerical duties. Six days later, they received authorization from the Secretary of the Navy to do so.

Word of this new policy spread quickly through newspaper and word of mouth. On August 13, 1918, thousands of women across the country marched into recruiting offices to join the Marines. Opha Mae Johnson was first in line at her local recruiting station and had the distinction of being the first woman enlisted into the US Marines. Johnson was hired as a clerk in the office of the Quartermaster General. By the time the war ended, she was a sergeant, the highest-ranking female Marine.

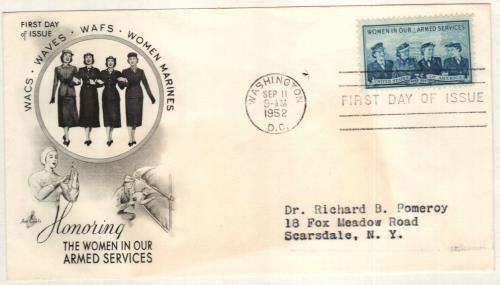

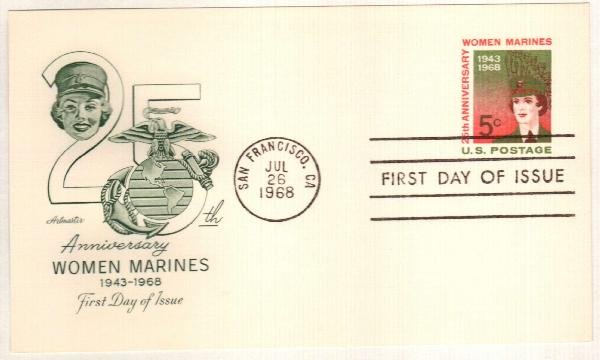

The majority of female Marines (called Marinettes) worked as bookkeepers, accountants, and typists. Though thousands of women volunteered, the Marines had strict guidelines – the women needed to have specific experience and pass a physical examination. By war’s end, a total of 305 women had enrolled and served in the Marines.

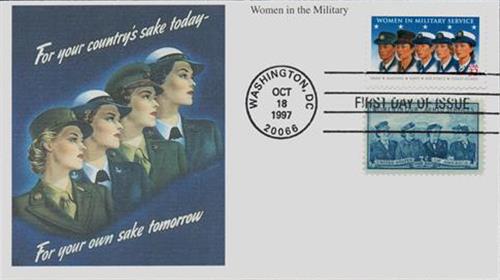

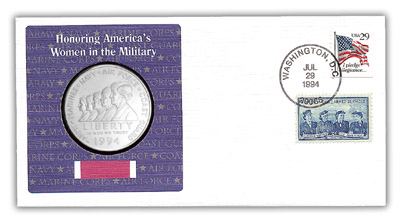

When the war ended and the men returned home, most of the Marinettes were discharged, while some opted to finish out their four years. But the Marines no longer recruited for women. However, women would be mobilized for the Marines once again in 1943. During World War II, over 22,000 women joined the Marines performing 200 different jobs. This time their work extended beyond clerical jobs to include parachute riggers, mechanics, radio operators, mapmakers, and welders. While most of the Marinettes were once again demobilized after the war, Congress passed the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act in 1948, permitting the enlistment of women into the regular component of the Marines and other armed services.