Women Marines: 25th Anniversary

reprinted from the Marine Corps Gazette Vol 52 Issue 2

Author: Pat Meid

A time to reminisce but even more to look at a new generation of Women Marines making its own contributions, blazing new trails, and serving with distinction.

ALTHOUGH women traditionally tend to be chary and somewhat imprecise when it comes to acknowledging birthdays, an entirely different situation exists this year with Women Marines.

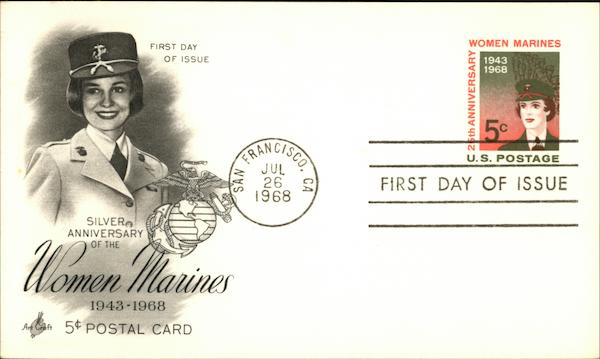

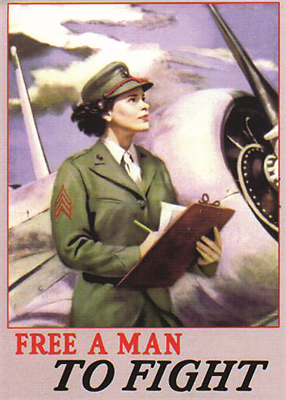

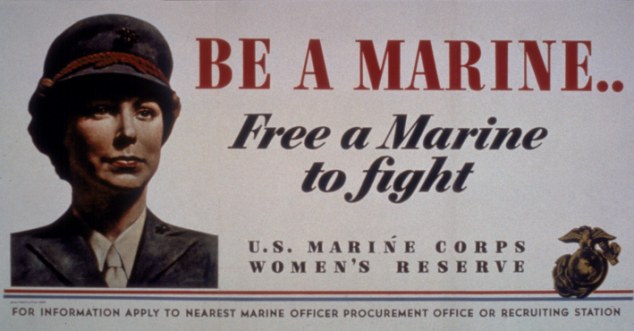

For on 13 February 1968 they are joining their Director, Col Barbara J. Bishop, and her staff, in observing the 25th anniversary of the Women’s Reserve established in 1943. Approximately a Marine division of American women enlisted within the next 16 months under the impelling wartime call, “Free A Marine To Fight.”

Again, perhaps atypically, distaff Marines past and present observe a second red letter day in 1968: 12 August marks the 50th Anniversary of their World War I counterparts, the Marine Reservists “F” as they were called in their day. It was on this date, in 1918, that secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels authorized the enrollment of women to replace male Marines needed for field service in France. Attired in high-buttoned shoes, skirts nearly to their ankles, but otherwise traditionally-styled Marine uniforms, 305 venturesome and patriotic young women answered the government’s call to work in Marine Corps offices in Washington, D. C. and the recruiting stations.

Observance of Women Marine silver and golden anniversaries comes at a time, appropriately, when increased professional stature, job opportunity, and advancement for women officers of all services is now practically a fait accompli. On 8 November 1967 President Johnson signed a bill giving women officers of the Armed Forces equal promotion and job opportunity with their male counterparts.

The President’s act struck a host of retirement and separation restrictions formerly applying to service women, opened quotas in the upper ranks, and made it possible for a woman to be spotpromoted to a general or flag officer rank when appropriate for a particular assignment.

A host of challenging innovations have been welcomed by WMs during the past several years:

* New overseas duty billets in Vietnam, Japan, Okinawa.

* Removal of restrictions from nearly a half dozen stateside and foreign duty locations for lower-rank WMs.

* Increased opportunities for specialized, highlevel advance schooling including Monterey Defense Language Institute and the Amphibious Warfare School.

Percentage-wise, the Marine Corps has a greater number of WMs in the top two enlisted pay grades than any of the other services. In the Marine Corps this rate is 2.2 percent, compared with the Army’s 0.9 percent; Navy, 0.6 percent; and Air Force, 0,4 percent. Moreover, there is indication that a greater percentage of enlisted women rise to commissioned status than in the other women’s components.

Presently, nearly 200 Women Marines (28 officers, 167 enlisted) serve at nine overseas locations. These are FMFPac, Camp Smith, and MCAS, Kaneohe Bay, both at the island of Oahu, Hawaii; MCAF, Futema and Camp Butler, in Okinawa; MCAS, Iwakuni, Japan; Saigon, in Vietnam; Manila, the Philippines; and Panama City.

In the European theater, duty assignments are at London (U. S. Naval Forces, Europe, or NATO) : Naples (Allied Forces Southern Europe, AFSE) ; and Stuttgart (headquarters for the U, S. European Command, EUCOM, transferred there from Paris about a year ago).

Besides the new WesPac assignments, new duty stations for AVMs that have opened up nearer home within the past 15 months include the air stations at Beaufort, S. C. and Yuma, Ariz.; the air facility at Santa Ana, Calif.; MCB, 29 Palms, and two supply centers at Barstow and Albany, Ga. The latter was activated on 13 September with a ribbon cutting ceremony attended by the Director, Col Bishop, and SgtMaj Ouida W. Craddock.

Women Marines are used interchangeably with male Marines to satisfy manning requirements in non-combat billets of any command. The outlook is for increasing the number of these overseas assignments. For example, in a recent Director’s report to the Commandant a total of 24 officer and 136 enlisted billets at nine duty stations were identified as suitable for Women Marines. This included existing installations as well as ones proposed at Beirut, Frankfurt, and Yokosuka.

Since the Women’s Armed Services Act of 1948 (another anniversary!) authorizing a relatively small number of women to remain permanently on active duty (a hedge against the wartime experience of having to provide “instant Women Marines”), the size of the women’s component has depended largely upon the needs of the Marine Corps.

A buildup from less than 1,500 active duty AVMs (965 more in the Reserve) at end of 1964 to a projected FY 1969 strength of 2,900 has been in process for the past several years. The impetus is two-fold, stemming both from current Marine Corps involvement in Vietnam and the 1965 Pepper Board recommendations for greater utilization of Corps womanpower. Actually, there are fewer women on active duty today than on 30 September 1953 when WMs reached their peak Korean strength of 2,600 enlisted and 187 officers.

With passing years that relegate not only World War II but even Korea to the history books, there is a steady stream of outstanding, dedicated Women Marine senior NCOs and officers who are retiring. (Symptomatic of the times: a still youthful-appearing WM LtCol, commissioned in 1943 and on duty in 1950, who observes goodnaturedly, “These days when I go on ADT and these youngsters ask what war I was in, I just tell them ‘Korea.’ “)

More and more, a new generation of Women Marines is taking over-a generation which makes its own contributions, blazes new trails, and serves with distinction.

Training Program

Unlike officer indoctrination [this subject is covered in a separate article in this issue], Marine Corps Recruit Training is a year-round, continuous process at Parris Island. Here in a fast-paced seven-weeks of uncompromising discipline, more than 1,400 casual civilians are transformed into snappy Women Marines every 12 months.

In fact, enlisted recruiting in the past several years has maintained a record-breaking trend of its own. The personnel goal has not only been achieved, but consistently exceeded, with 102 percent of quotal At the Woman Recruit Training Battalion, directed by LtCol Ruth J. O’Holleran, CO, 13 seven-week training classes (properly, a “series”) are scheduled per year. A series consists of two platoons, numbering 56 girls each, most of them in the 18-21 age bracket. Upon completion of recruit training, some WMs receive advanced schooling, but the majority go to their first jobs at new duty stations. Honor graduates go as PFCs, having proudly stitched on their uniforms that first red or dark green chevron.

One aspect of WM training in both officer and recruit schools has received some over-emphasis in recent news reports. Public interest is understandably piqued by the idea of a new Marine Corps grooming course, modeled after Pan Am’s stewardess training. But the idea isn’t really new. Traditional Marine Corps insistence on spit and polish has always dictated a smart, attractive, military appearance in its women. What is new is the way grooming is being in tight. In the past, the subject was dealt with from the lecture platform, more or less in a general discussion. Today, individual attention from specially trained WMs makes grooming a personal challenge for each woman trainee. Personal analysis and instruction is provided on hair, makeup techniques, weight control, posture, voice projection. There are even tests. Everyone connected with the program is pleased about the results obtained with the new approach.

Along with Women Marines from the newest training classes celebrating the February anniversary date is that elite group of early Reservists “F” from World War I. Of the original 305 enrolled, at least 192 are known to be still living. Fifteen who reside in the greater Washington area have been invited to take part in the festivities scheduled by HQMC and the Women Marines Association (see page 42).

Opening the ranks of the Corps to distaff Marines back in the days of 1918 was based on a government estimate that “40 percent of the work at Headquarters, Marine Corps can be performed by women as well as men.”

Women were enlisted primarily for clerical and messenger duties at Headquarters in the paymaster, quartermaster, adjutant & inspector, and Commandant’s offices. A few also replaced men in the recruiting stations in New York, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Portland.

A strong sense of patriotism motivated women, as well as men, to join the Marine Corps. Many had husbands, brothers, or fathers already on the front lines in France. In one family the parents so regretted they had no sons to send to war that their twin daughters promptly answered a newspaper ad which announced the Marines were seeking women for the Corps.

Typical Marine Corps standards of precision not only governed the dispatch with which they performed their office duties, but also extended to their smart appearance both in and out of marching units. They were instructed early every morning in the “simpler drill movements” by a no-nonsense Marine noncommissioned officer and participated in victory parades and other ceremonies in the Nation’s Capital.

These pioneering female Marines from 18 to 40 years of age received the same pay and allowances as enlisted men of corresponding rank. Dedication paid off. Those who proved “capable and industrious” could be promoted to the ranks of PFC, corporal, and sergeant, the highest grade obtainable. Their uniforms, both summer khaki and winter greens, closely followed the styling of male Marines, even to their overseas caps and widebrim campaign hats which both bore the regulation globe-and-anchor insignia.

World War II

After a lapse of nearly 25 years and due to increasing pressures of manpower shortages in World War II, the Marine Corps again called on women to serve.

Official announcement of the new program was made 13 February 1913 by the Corps’ 17th Commandant, General Thomas Holcomb. Prospective candidates ranged from school girls, widows of two Marine majors recently killed in combat, office workers and students, to grandmothers. In the Nation’s Capital, more than 100 women filed applications the first two days after enlistments opened. One recruiting official complained that the overload of applicants was causing his office staff to “get behind in their work.”

Prior to public announcement of the program, Mrs. Ruth Cheney Streeter was sworn in as Major, USMCR, to head the new Women’s Reserve. For two women, however, this was the second wearing of the Marine green. One returning reservist was Captain Lillian O’Malley Daly, a member of the small handful of officers commissioned directly from civilian life in early 1943 to fill priority billets. The other was Mrs. Martrese Thek Ferguson, an honor graduate of the first candidates’ class that trained at Mount Holyoke College in May 1943. Later, as a lieutenant colonel, she became commanding officer of more than 2,000 women at Henderson Hall.

The Navy Department generously offered to help its new sister service get off to a good start, even to the point of providing 19 recruiting officers who went on duty immediately (in their WAVE uniforms) to help process the avalanche of enlistments from women who wanted to be women Marines.

In February 1944-a year after formation-the Women’s Reserve had grown from eight officers to a strength of nearly 15,000. They were on duty at every Marine post and station in the United States (WRs later served in Hawaii, too) and recruiting districts. The original prediction of “more than 30 different kinds of jobs” had grown into over 200. In addition to administrative billets, the women had been trained in specialist fields such as communications, disbursing, quartermaster, post exchange, food services, and aviation skills ranging from parachute rigger to Link training operator.

By June 1944 the Women’s Reserve had scored another “mission accomplished.” It had enrolled its full strength of 18,000 enlisted women and 1,000 officers. By this time the WRs constituted 85 percent of the enlisted personnel at Headquarters, Marine Corps and from one-half to two-thirds of the enlisted strength at major commands. And although last of the women’s military services to be organized, the Marine Reserve became the first to reach its announced recruiting goal.

Exactly how many Marines the Women Reserves freed to fight was often a subject for speculation. Their peak strength-nearly 19,000approximated that of a World War II division. General Alexander A. Vandergrift, second wartime Commandant, once remarked that the Women Reserves could “feel responsible for putting the 6th Marine Division in the field; for without the women filling jobs throughout the Marine Corps there would not have been sufficient men available to form that division.”

Postwar Women’s Reserve

Early in 1946, when total demobilization was imminent, the Marine Corps realized the desirability of maintaining a small group of trained personnel on duty to work out plans for a postwar Women’s Reserve. It was felt that such an organization would insure that a future emergency would never again make it necessary to “start from scratch.”

Congress thought likewise. Passage of the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act, in June 1948, authorized the acceptance of women into the Regular Marine Corps for the first time. During the interim period, from 1946 to 1948, fewer than a hundred volunteer Women Reserves were on active duty. And yet they were the ones whose continuity of service bridged the gap between the wartime reserve and permanent reserve-and-regular women’s component of the Corps. It was they who, in effect, established, the 13th of February 1943 as the lasting Anniversary date of Women Marines.

Late in 1948, the first group of three former wartime Reserve officers and eight enlisted women were sworn in as members of the Regular Establishment. One of the returning officers was Major Julia E. Hamblet, who had served as Director of the Women’s Reserve during the immediate postwar transition period. Also transferring to the Regular Marine Corps was Colonel Katherine A. Towle who, relieving Colonel Streeter, had served briefly as the second wartime Director from 7 December 1945 to 12 June 1946. This time her title was director of Women Marines.

In 1949 the first postwar recruit and officer training classes were started and opened to qualified women without prior military service. Another postwar innovation for distaff Reservists was the woman’s platoon. Beginning in Kansas City, in April 1949, a total of 13 were established as part of the men’s Organized Marine Corps Reserve units in major cities throughout the country. Women members attended regularly scheduled drills and trained in specialties such as classification, disbursing, supply and administration. Probably the highpoint of the year was the two-week Reserve annual summer field training program which they attended, like the men.

The Korean Era

Reservists joining the women’s platoons could hardly have foreseen they would soon be living up to the World War II motto “Free A Marine To Fight.” But in the summer of 1950 when the Korean War suddenly erupted and OMCR units were called up the Women Reserves were also mobilized-for the first time in history.

By August 1950 all 13 WR platoons had reported, as units, for duty at major Marine Corps commands. Their numbers did not approach the strength of the Women Reserves of World War II; yet the women accomplished ‘their mission by stepping into jobs for which their reserve training had prepared them. Like the women of two previous wars, they freed Marines for combat duty.

Following the Korean War, seven new Organized reserve platoons were activated, bringing the total to 20. The platoons continued as the backbone of Reserve training for women until 1958, when budget limitations forced their disbandment. Approximately a third of the women who were attached to the deactivated platoons affiliated with their parent men’s OMCR units. Other women reservists transferred to inactive reserve status or continued as members of the Reserve Volunteer Training units.

Since 1943 more than 40,000 women have trained as Women Marines, both regular and reservist, for service during and following World War II. Active-duty strength of the women’s component is comparatively small-set by law at two percent of total strength of the Corps. But their selection and training provides the Marine Corps with a continuing source of capable, professionally-minded women ready to meet mobilization needs such as occurred with rapid expansion in June 1950 during the Korean War.

Nearly two decades later, with the Marine Corps heavily committed today in Southeast Asia, women of the Corps continue their traditional role of performing vital jobs that will free more Marines for combat. Hawaii, once their farthest, outpost, has become a stopover for women on the way to duty in Okinawa and beyond. In stateside and overseas assignments, women of the Marine Corps not only continue the traditions of 25-and 50 years but set new ones undreamed of by their predecessors.

This Anniversary year is a time to look back with pride, yes, but even more to look and work toward the future.

Women Marines Association

The first meeting of the Women Marines Association was held at the Shirley-Savoy Hotel, Denver, Colorado, 25-28 July, 1960. The founders were Maj Jean Durfee, Marion A. Hooper Swope, Mary Jeane Olson Nelson, June F. Hansen, Lois Lighthall, Ila Doolittle Clark and Barbara Kees Meeks. The meeting of many interested persons was held and Constitution and Bylaws drawn up and presented for ratification.

The purposes of The Women Marines Association are:

* To foster, encourage, and perpetuate the spirit of comradeship and to counsel and assist and to mutually promote the welfare and well-being of all women who have served in the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, the United States Marine Corps Reserve and/or the United States Marine Corps.

* To promote duties of citizenship and civic leadership, and to encourage them to serve their country as faithfully as citizens as they have served it as military personnel.

* To foster patriotism and to perpetuate the traditions and the esprit de corps of the United States Marine Corps.

* To promote through education, guidance and incentive, among our American youth, the national traits of idealism, integrity, purposefulness and uncompromising loyalty and patriotism of our forefathers, the rightful heritage of every American.

* To cooperate with and/or support any organization or individual who strives toward increasingly raising (a) the moral standards of our country, and (b) its position of prestige and world leadership.

* To promote and cultivate greater understanding and stronger action among the women of the world for lasting peace.

Thank you to the Marine Corps Association for allowing us to reprint the articles written about our women Marines.