MCRD WRBN 1943-1946

‘Serving the Nation and Making a Difference’

BY: Carl Frederick Huenefeld II

Colonel, USMC (Ret)

The big stories of the clash of nations and ideologies are the province of real historians. This however, is a small story about a little piece of how that all came to be at one small base, and of the almost 700 women who served there as Marines between 1943 and 1946 and set a standard for the Marine Corps of today. This story is specific to a place, the Marine Corps Base, Naval Operating Base, San Diego California – now the Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego.

In 1916 Congress appropriated funds to purchase land for a new base for the United States Marine Corps in San Diego. It was the first purpose-built base for Marines on the West Coast, a launching pad for expeditionary forces and a home base where they trained. Construction of the new facilities began in 1919 and by the mid-1920s a small base had risen from the tidelands in the area called Dutch Flats.

The Marine Corps of the 1920s was a much different force from that we know today. It was much smaller, with less than 18,000 officers and Marines on active duty and still organized around service with the Navy’s fleet. There were ships detachments and small unit’s stationed at Navy bases for duty in support of Fleet Advanced Force Operations. The city of San Diego was different as well. It was essentially a small coastal city of less than 75,000. The first direct rail line to the East had recently been opened and lumber, fishing and tourism were the drivers of the economy.

The new Navy and Marine presence in San Diego certainly heralded change, as did the dredging of the bay and the mouth of the harbor, but the real agent of change was the opening of the Panama Canal and the early refocus of strategic attention on the Pacific with its increased opportunities for trade and commerce. Regrettably, revolutionary change was not limited to peaceful endeavors. The rise of the Japanese Empire as a true regional power brought war to the Pacific in 1941, and with it a complex reorienting of the military might of the United States to fight wars in both the European and Asian theaters – irreversibly changing San Diego.

The Japanese had effectively proven their naval competence in 1905 when, under Admiral Heihachiro Togo, they destroyed the Imperial Russian Baltic Fleet in Tsushima Straits. The treaty that ended the Russo-Japanese War ceded control of Korea, Sakhalin Island and China’s Liaotung Peninsula to the Japanese. The Japanese broke out of Liaotung and occupied Manchuria in 1931 and invaded China proper in 1937. However, local San Diego Marines felt the effects of the deteriorating situation nearly 10 years before in 1927 when ‘San Diego’s Own’ 4th Marine Regiment, Colonel Pendleton’s Regiment that had first made a Marine Corps home in San Diego was ordered to China.

By 1940 China was fully embroiled in a war with Japan. Germany had taken Poland and was poised to eventually break out into Western Europe. The United States was trying to avoid being entangled in the growing crisis and was, at least officially, observing strict neutrality. The Marine Corps had less than 30,000 officers and men and the US armed forces only totaled 460,000 men; roughly the size of the Anglo-French Force that was evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk that spring. By the time Japan surrendered five years later, there were more than 12 million American men and women in the armed forces and the United States was the undisputed premier world power. That convulsive growth was as incredible as it was disruptive.

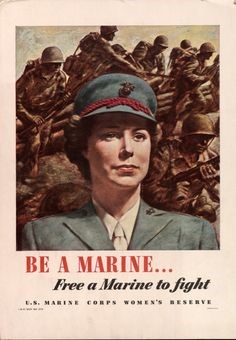

The demands of a global war could never be met by the small peace-time US military and recruiting along with the selective service conscription programs started in full force. By early 1942 it was apparent to US leaders that the male population wasn’t going to be adequate to meet the demands for personnel. By current standards it may sound sexist or at the very least patronizing to characterize women as serving only to ‘Free a Man to Fight’. However, this call to arms resonated with women at the time, and in February 1943 the Women’s Reserve (WR) of the United States Marine Corps was activated.

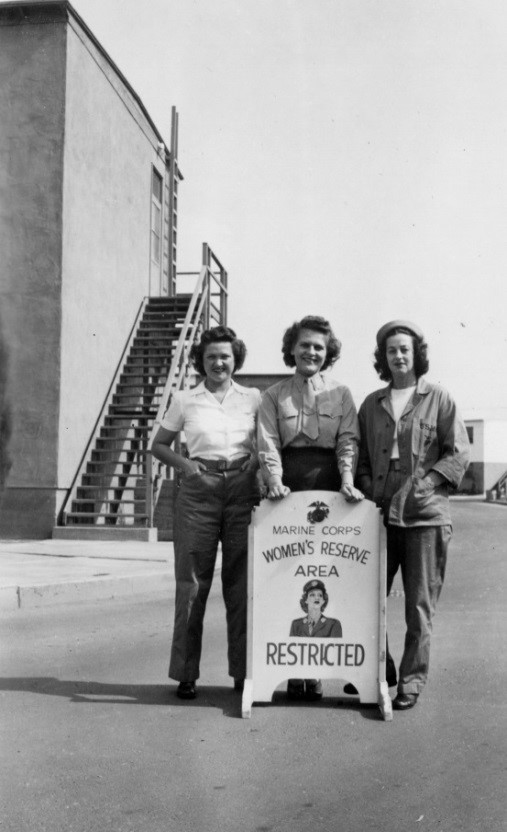

Activated Women’s Reservists in the Marine Corps were initially trained at Hunter College in New York and Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts, but by July 1943 a training camp for them had been established at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. The first women began arriving at Marine Corps Base San Diego in September 1943 and more arrived virtually every week. By February 1944 there were 3000 women serving in the San Diego area, not only at MCB, but also with Marine air units at North Island, Camp Elliot (now MCAS Miramar), Camp Mathews (now the site of UCSD), and a myriad of smaller postings throughout the county.

The 300 women stationed at MCB were led by Lieutenant Dorothy Miller. What had been Lott Field just inside Gate 4, MCB’s recreational fields, gave way to new construction of WR barracks, quarters for their officers, and other battalion facilities. By August 15, 1945, VJ Day, there were 661 female enlisted Marines and 19 female officers aboard the installation, enough to free an infantry battalion of male Marines for combat. Corps-wide, 18,850 women freed up the equivalent of almost a division. According to Headquarters Marine Corps, by the end of the war women served in more than 225 occupational specialties, filled 85 percent of the enlisted jobs at the Marine Corps Headquarters and comprised one-half to two-thirds of the permanent personnel at major Marine Corps posts.

They came from around the nation, from varied backgrounds and for a variety of reasons, and served in many different ways across the Corps. Specifically in San Diego, they worked in the message center, the film library, in administration and separations sections, payroll, and the recruit classification sections. Additionally, women Marines ran the base exchange, served as drivers and mechanics in the motor pool, worked in the public affairs office, in the quartermaster’s department, as base education and recreation officers, and even as the secretary for the exclusively-male sea school. The performance of women in these, and a number of other jobs, conclusively demonstrated their versatility and commitment to the mission of their command and the war effort.

While they worked with male Marines all day, their lives were otherwise fairly segregated. They had, of course, a separate barracks, a separate small post exchange with an associated recreation room, a separate chow hall, medical facility and a separate woman-only section in the theater. In San Diego there was a separate servicewomen’s United Service Organization club and a servicewomen’s transit hotel. They wrote their own columns in the MCB paper, the Chevron, originally called ‘Skirtin the Base’ then ‘Women’s Reserve – Views and News,’ and later as ‘Nobbin with Natalie’. Their athletic prowess showed when they won the 11th Naval District Softball Championships in 1944 and 1945, and fielded teams in the Service Women’s League for basketball as well as bowling and shooting teams, and a 50-woman fancy drill platoon.

Demographically they were very different from their male counterparts. The minimum age for enlistment was 20 (while men could enlist at 18 or even 17 with parental permission) so they were a little older. A higher percentage were married, almost all to servicemen, most of them had worked before joining, and they were predominantly from north of the Mason-Dixon Line. They came from a society still adjusting to new roles for women which is part of the reason why Rosie the Riveter was seen as groundbreaking. Yet by the end of the war the demand for labor had overshadowed some of the barriers and 18 million American women were in the work force, comprising nearly one third of all civilian employment.

The women at MCB, like elsewhere in the Marine Corps were organized in a separate command directly supervised by woman officers to provide augmentation to existing organizations aboard the MCB. By December of 1943 there were enough women assigned to the MCB to justify the activation of a WR Battalion. The new battalion was initially commanded by an experienced male officer, Major Troy Nelson, with Lieutenant Miller as his executive officer. Shortly after Miller’s promotion to 1st Lieutenant in February 1944, she relieved Major Nelson and became the battalion commander. She was promoted to captain and then quickly to major in June of 1945, receiving a promotion about every 8 months, a direct reflection of the challenges of building an organization from the ground up.

She remained the commander, where she was by all indications liked and respected, until she was released from active duty during the demobilization in April of 1946. Major Miller returned to Iowa where she married and began a career in advertising, mainly for radio stations, and eventual began promoting events and development for the Chamber of Commerce in Daytona Beach, FL., where she passed in 1998.

Dorothy Miller

Another woman who answered the nation’s call was Marilyn Wilson, who enlisted because her husband was on a US Navy ship in the Pacific. She simply needed a job and a place to live other than with her mother while she waited for him. Marilyn trained at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, in the fall of 1944, went to Motor Transport School and was assigned to MCB San Diego. Her service was only about a year long. It was generally routine consisting of driving and delivery duties, but it was also incredibly transformational for her personally. After her active service, Marilyn raised three sons and then attended UCSD where she earned a bachelor’s and master’s degree. She taught in San Diego city schools for twenty years then at the State Department’s American School in Lima, Peru, after her husband passed away. Still living in San Diego she believes her Marine Corps experiences taught her to be less selfish and kinder as well as how to work with other people with other experiences and backgrounds in a team. In a 2012 interview, 66 years after her end of service, Wilson concluded by saying ‘I’m just proud to say I’m a Marine. I’m a Marine!’

The simple idea that a Marine was a Marine, regardless of gender, was not necessarily accepted in 1943. Enlistment requirements were different from those for male Marines, as was the understanding of what was or could be expected in terms of service. Initially, there was uncertainty about what authority female officers and noncommissioned officers would hold over male Marines, but the status of women was clarified in April of 1944 when HQMC published guidance that answered any questions about these women’s rank and authority. In short, their authority was no different from that of their male Marine counterparts. Legal authority notwithstanding, women were not necessarily accepted as equals in the Marine Corps. Other questions that seemed important at the time involved issues like make-up, uniforms, and conduct, but eventually the questions were all answered. The Marine Corps dealt with the mechanics of having women in its ranks; the women proved their own worth.

TSgt (Bn SgtMaj) Grace G. Smith on the day of her promotion

A telling turning point may have been in 1944 when a Life Magazine reporter asked the Commandant of the Marine Corps, General Holcomb, what nickname women in the Marine Corps would use. His response left no room for interpretation. “They are Marines. They don’t have a nickname and they don’t need one. They get their basic training in a Marine atmosphere at a Marine post. They inherit the traditions of Marines. They are Marines.”

Though women didn’t go into combat, women of any of the services weren’t even allowed to leave the continental United States until late 1944, the war still touched them in other ways. Sadly, many servicewomen had family members; husbands, brothers or fathers wounded or killed on active duty. Many of their stories tell of a member of the Woman’s Reserve being informed of the death of a spouse or loved one and the impact of that news on not only her, but her friends who closed ranks to support her. They saw, if second-hand, the effects of combat. They met troopships, hospital ships and air medical evacuation flight’s to provide follow-on transportation, administrative or separations support, or in the case of public affairs Marines, to simply help combat Marines tell their stories. Much of the trauma these men had experienced in combat was shared.

One example of this experience was Ann DiValerio, of Chicago, Illinois who joined the Marine Corps in August of 1943 following her then fiancé who was already a Marine serving in the Pacific. After training Ann served in the MCB base library – an assignment she was not initially enthusiastic about. Her sense, no doubt sharpened by the death of her fiancé who was killed in action on Tarawa, was that she wanted to be more directly involved in the war effort. That view was shared with others, quite possibly by those women assigned as beauty parlor operators in support of other women on MCB, but they were all part of making the war machine work during this period.

While the value of their critical contribution to the war effort was widely acknowledged their experiences in service were not universally positive. Many male Marines were either dismissive or outright hostile to the idea of women wearing their ‘Marine Corps Green’, but the demands of the time were such that bad attitudes, for the most part seemed to have simply fallen by the wayside. Everyone was too busy and working too hard to remain ungrateful for support, regardless of where it came from. Women came into the MCB commands, found their place, and started to contribute to the mission. Soon those contributions began to be noticed, even if in some cases grudgingly. The best known example of this transformation of attitudes came, again, from the top. In a simple statement after the war, General Holcomb said “Like most Marines, when the matter first came up, I didn’t believe women could serve any useful purpose in the Marine Corps . . .Since then, I’ve changed my mind.”

The downsizing of the armed forces at the end of the war also meant the end of the perceived need for women in the Marine Corps. Demobilization was both welcomed and regretted, as women of the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve changed back to civilian clothes and went home to resume their lives. The view seemed to be that the women had served and were going home just like 90% of the men who were in uniform at the end of 1945. Articles in the base paper expounded on the question of what WRs were looking for in the ideal husband and how to convert their uniforms to civilian clothes which were in short supply.

Page one of “The Chevron” for May 17, 1946, reported on Corporal Laura Picketts, suitcase in hand, locking the door on Barracks 338, symbolically closing a part of the history of Marines in San Diego. Corporal Picketts returned to her home in Seattle a changed woman, having served her country as a Marine. She married Gordon Haskell, a Marine Corps fighter pilot with four years combat experience in the Pacific. Major Haskell was recalled to active service for the Korean War and was sadly killed in action in December 1952. But there were 690 stories, one for each woman in the WR battalion and each worthy of being told.

The experience of having women serve had changed not only the people involved, but the Marine Corps itself, social attitudes in the American public and even the underlying culture. Those changing attitudes and the persistence of the women who had served, and their supporters, created pressure to incorporate women more fully into the armed forces. The deactivation of the last of the women of the Women’s Reserve Battalion marked a shift from a war-time Marine Corps back to a much smaller male-only force, but it was now a Marine Corps that had actual experience with women in uniform. It wasn’t long before women were back – for good.

While the World War II veteran women reservists were essentially a war-time contingency force they were also an in-place cadre of trained Marines. In July of 1948 the US Congress passed legislation admitting women into the regular component of the armed forces. Initially the Marine Corps intended to admit 100 female officers, 10 Warrant Officers, and 1000 enlisted women with priority for enlistment going to women veterans.

On September 1, 1950 1st Lieutenant Kathryn Snyder reported for duty in the Manpower Section of Base Headquarters and by the end of the year there would be 39 women Marines serving in San Diego. This time Women Marines, at what was by then Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego, were fully integrated into standing organization on the depot, mainly in Headquarters and Service Battalion.

The story of the women of the Women’s Reserve Battalion of Marine Base, San Diego during the Second World War is not well known, even among Marine. The ladies of the battalion came as Marines, did what needed to be done, and quietly faded into the wave of demobilization after the war’s end. They left a legacy that is not women’s history or women Marine history as much as MARINE CORPS HISTORY, and they remain part of the fabric of MCRD today. We who wear, or have worn, Marine Green all owe them a debt of gratitude and they should not be forgotten.

- Author’s personal note: I joined the Marine Corps in 1971 – a Corps that was in many ways still dismissive of the contributions women brought, and could bring to our Corps. I shared that view and today I’m not ashamed that I had that attitude as much as embarrassed. Over the forty years I was on active duty, women, in a generally quiet but persistent way, made themselves ever more indispensable and indistinguishable from any other Marine. By the time I commanded an Artillery Regimental Headquarters Battery during the Gulf War we simply could not operate without the women who served in our Combat Support and Combat Service Support units. I had 40+ women in my little command in Saudi Arabia and in the assault into Kuwait. They were a credit to our nation and our Corps – as good as any group of men I have ever served with. Near the end of my career I was asked to serve as the Chief of Staff for the Marine Corps Recruit Depot, San Diego and the Western Recruiting Region – my Commanding General was Brigadier General, later Major General, Angela Salinas, a driven lady and a great Marine leader. I would not suggest that we’ve got it right at this point, but I am certainly proud of how far we have come – Marines are Marines. Semper Fidelis.

Carl Frederick Huenefeld II

Colonel, USMC (Ret)

References, Attribution and Appreciation

All images are the property of, and used with the permission of the United States Marine Corps.

Extensive use has been made of archive copies of the MCB San Diego Base Newspaper ‘The Chevron’ from 1941-1950.

Marine Corps History Division Archives

Internet-Based Genealogical Research on Marines specifically identified

Oral History Transcripts and personal communications with members of WRBN SD.

Cornell College Library, particularly Meghan Yamanishi Consulting Librarian for Social Sciences Cole Library, Cornell College of Mount Vernon, Iowa

Cedar County Historical Society, Tipton Iowa, particularly Sandy Harmel

The spectacular ladies of the Command Museum., MCRD San Diego: The Director, Barbara Mccurtis, along with Ellen Guillemette and Joanie Schwarz-Wetter

Women Marines: The World War II Era by Peter A. Soderbergh. Published July 22nd 1992 by Praeger

Women’s Marine Association Network, particularly Maria Rodriguez-Callejas, President of the CA-2 San Diego County Chapter.