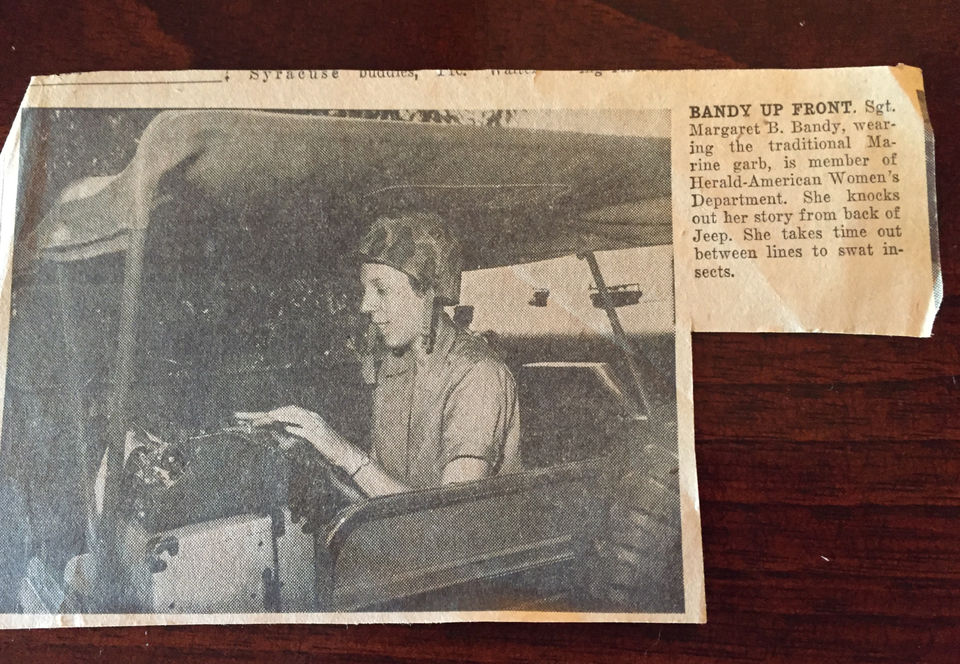

Liverpool, N.Y. — The moment that changed Peg Bandy’s life was 80 years ago.

But she remembers it like it was yesterday.

She was watching an uncle pack up to go on a military training expedition during World War II. I want to do that, she said.

“He said, ‘Well Margaret, they’ll never let women in the military. So you can forget about that,'” Bandy recalled.

He was the first person she went to see after she completed boot camp with the U.S. Marine Corps Women’s Reserve during World War II.

“I said, ‘You’re wrong,'” she said. He said, I guess I am.

“And he was very proud of me,” Bandy recalled, sitting in the recliner of her Liverpool home.

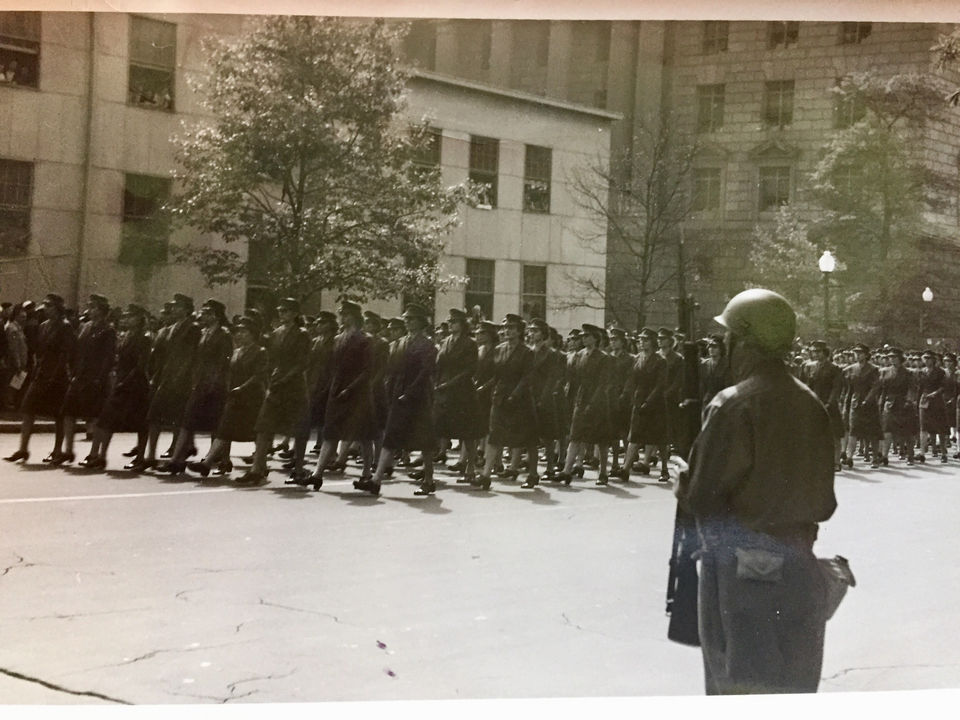

Now 97, Bandy, who was a sergeant during World War II, will be boarding an Honor Flight Saturday to Washington, D.C., with other female veterans.

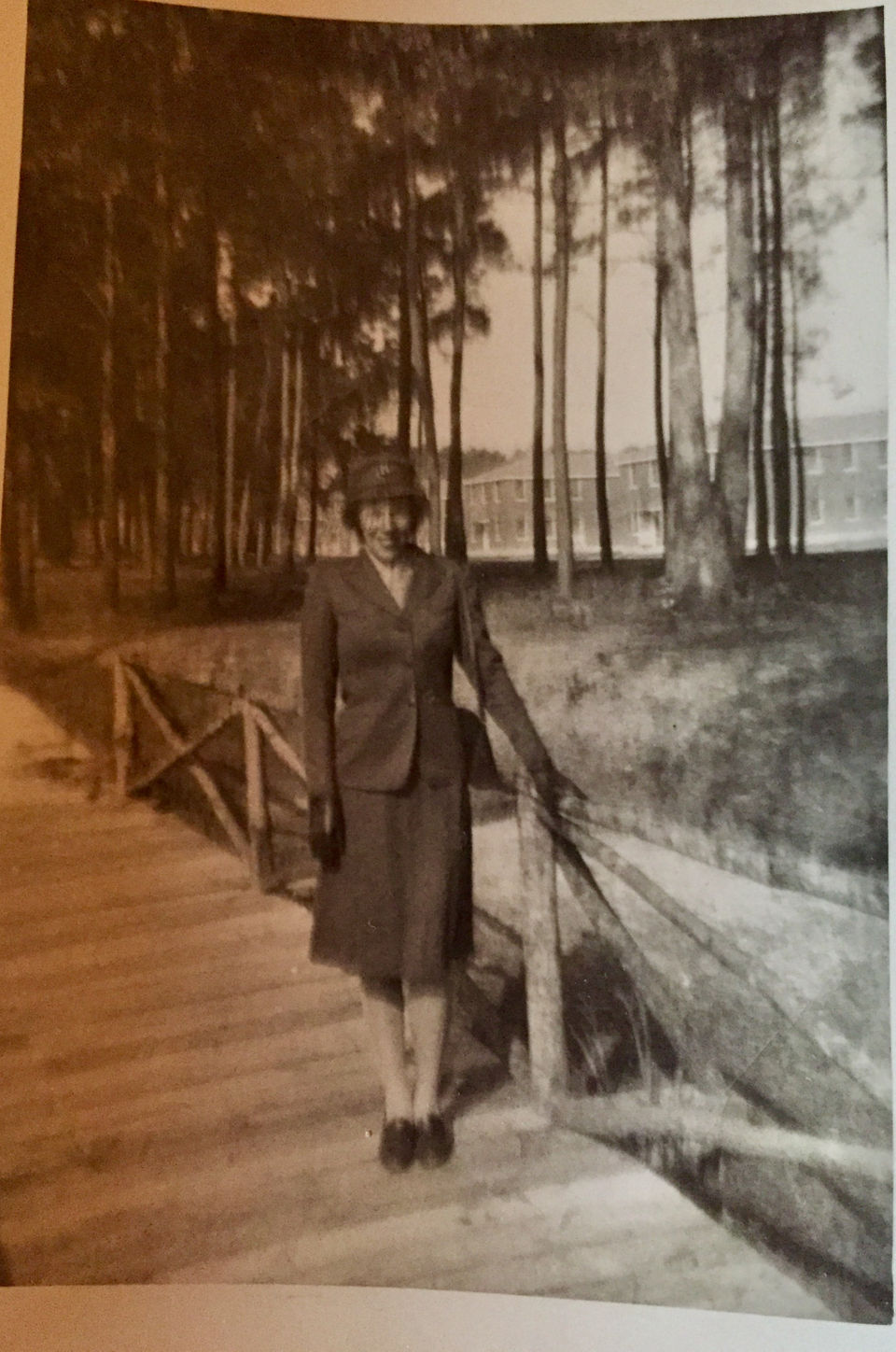

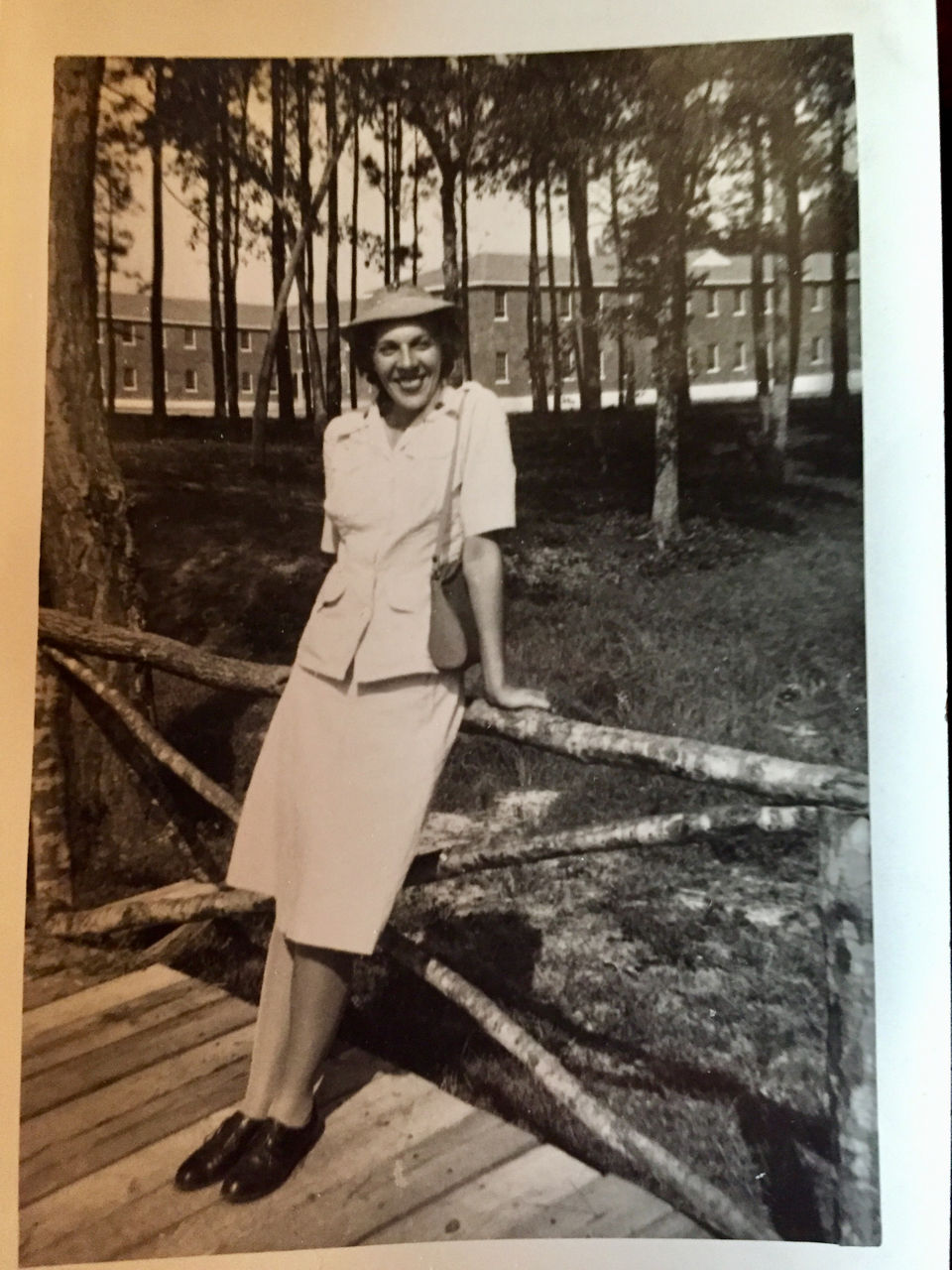

Bandy, then Margaret Bittel, was one of 22,000 women who were allowed into the U.S. Marine Corps during World War II.

Women were first allowed to enlist in the Marines during World War I. That was an experiment that ended with that war.

During World War II, women were again allowed to enlist, mostly to take over office jobs stateside. After the war, Bandy left the Marines, where she was a sergeant. But she was convinced to join the reserves when she returned home. She became the first woman to be sworn into the reserves in Syracuse.

In that position, she was a young woman working with all older men. They were professionals who had been hired by the Marines. But she said she never, at any point, recalled anyone treating her poorly or unfairly because she was a woman.

In that position, she was a young woman working with all older men. They were professionals who had been hired by the Marines. But she said she never, at any point, recalled anyone treating her poorly or unfairly because she was a woman.