2023 Anniversary of Continuous Service of Women Marines

History of our Anniversary. (by Jeannine Franz and Gail Horn)

By the WMA History Committee

Happy anniversary lady leathernecks! Or, is it happy birthday? This is a common debate, but the answer is simple. Every year, the Commandant of the Marine Corps writes a letter to women Marines in recognition of the ANNIVERSARY of the Marine Corps Women’s Reserve (MCWR). This recognition used to be posted as a MarAdmin and now it is in the form of a letter that is sent to the Women Marines Association. The Marine Corps celebrates a birthday as the foundational organization, and women Marines celebrate a few different anniversaries of significant events relating to authorization to serve in the Corps.

February 13th is celebrated as a reminder of the event in 1943 when the Commandant, General Holcomb, announced the formation of the MCWR. Since that date, women Marines have served continuously on active service. Although all MCWR units were disbanded in 1946, there were a small number of women retained as the postwar MCWR for their experience and to provide continuity in the case of mobilization emergencies. These women were only permitted to fill clerical positions. On June 12 of 1948, the Armed Services Integration Act of 1948 was signed enabling women to serve full time in the armed forces. (A History of the Women Marines 1946-1977, p.6)

As far as being “born”, we could say we were born as Marines where we received our basic training, which began at the U.S. Naval Midshipmen’s School, Mt. Holyoke College, MA for officers; the U.S. Naval Training School at Hunter College, NY for enlisted; and later in 1943, all basic training for women Marines was moved to Camp Lejeune, NC.

Photo courtesy of Audrey L. Bennington

Mt Holyoke and Hunter College

During World War II, the United States Marine Corps Women’s Reserve (USMCWR) was established to support the growing needs of the Marine Corps. To help with this effort, two colleges in the United States, Mount Holyoke College and Hunter College, were chosen to provide training for women who were interested in serving in the USMCWR.

Mount Holyoke College, located in South Hadley, Massachusetts, was the first women’s college to participate in the training program. The college provided courses in subjects such as military protocol, drill and ceremonies, and weapons handling. The program was designed to prepare women for their roles as clerks, radio operators, and other administrative positions within the Marine Corps. The first group of 71 Women Marine Officer Candidates arrived 13 March 1943 at the U.S. Midshipmen School (Women’s Reserve) at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts. The Navy’s willingness to share training facilities enabled the Marine Corps to begin training Marine Corps Women’s Reserve officers just one month after the creation of the MCWR was announced.

Hunter College in New York City also participated in the training program and provided similar courses to prepare women for their roles in the USMCWR. These women were trained in various skills such as secretarial work, bookkeeping, and other administrative duties. The first woman to join in 1943 was Lucille McClarren.

Lucille Ellen McClarren was born on August 25, 1922 in Graceton, PA to Olive Hockenberry McClarren and Daniel McClarren. She had an older brother, Daniel Edwin, and three younger siblings: Harry, Wayne, and Loretta Jean. The McClarren children grew up in Nemacolin and attended the Nemacolin Elementary School. Lucille graduated from Cumberland Township High School (now Carmichaels Area High School) in 1940.

After graduation, Lucille worked as a stenographer for the U.S. War Department in Washington D.C., living in the city. After the creation of the MCWR, Lucille became the first woman to enlist on Saturday, February 13, 1943. McClarren was sworn in by Captain H.W. Branson of the Marine Officer Procurement Unit, and once on active duty, would receive a starting salary of $50 and a $200 uniform allowance.

The women who trained at these two colleges made a significant contribution to the war effort and served their country with distinction. They provided much-needed support to the Marines on the front lines and helped to free up male Marines for combat duties. The USMCWR was eventually disbanded after the war, but its legacy continues to be remembered and celebrated as a testament to the bravery and dedication of the women who served.

Training at Camp Lejeune

While it was originally thought that it would be beneficial to use existing Navy resources for Marine Corps Women’s Reserves recruiting and training, it quickly became evident that Marines are a unique breed. Having different aspirations than the Navy for their WAVES, the Marines soon found it necessary to have their own schools. But, as Colonel Mary Stremlow wrote in FREE A MARINE TO FIGHT: Women Marines in World War II, “A larger motive for moving MCWR schools to Camp Lejeune was the famed Marine esprit de corps. Camp Lejeune, where thousands of Marines were preparing for deployment overseas, was the largest Marine training base on the East Coast and offered opportunities for the women to observe field exercises and weapons demonstrations, and to see the faces of the young men they would free to fight.”

Photo courtesy of Mary R. Rich

The Marine Corps Women’s Reserve Schools, Camp Lejeune, North Carolina — officer candidate and boot training along with certain specialist schools — opened in July 1943 under the command of Colonel John M. Arthur. Officer candidates and recruits in training at Mount Holyoke and Hunter Colleges were transferred to Camp Lejeune. There, nearly 19,000 women became Marines during World War II.

Transporting all the trainees to Camp Lejeune was its own logistical nightmare. The recruits travelled to Wilmington, North Carolina, on women Marine troop trains of about 500, commanded by a woman lieutenant and two enlisted assistants. They arrived at the depot as civilians, but the transition to Marines began immediately. The women were quickly lined up, issued paper armbands identifying them as Marine “boots,” ordered to pick up luggage — anybody’s luggage — and marched aboard the train. The process accelerated at the other end where they were met by shouting NCOs who herded them into crowded buses to be taken to austere, forbidding barracks with large, open squadbays, group shower rooms, toilet stalls without doors, and urinals. (Hmmm, pretty sure it was like that in 1984 when I went to boot camp too, but it must have been quite a change from the college dorms…says, Gail Horn.)

Many of the MCWR recruits were wondering “What have I gotten myself into?!” The schedule was intense and left no time for remorse. General processing, medical exams, uniform fittings, and classification tests/interviews assessing abilities, education, training, and work experience were priority. Orientation classes and close order drill were scheduled for the first day and a strict training regimen kicked off with 0545 Revillee. (Wow, they got to sleep in!)

While the women Marines were working hard to try to find their spot in a male-dominated field, their male counterparts brazenly voiced their feelings about women in ‘their Marine Corps’. Shaping up a gaggle of “BAMs” (“broad-assed Marines”) was not what these male Drill Instructors (DIs) wanted to be doing with a war going on. One boot felt the DIs resented the women, “. . . more than a battalion of Japanese troops.” She may have been correct.

Many male Marines did nothing to disguise their resentment. Some women took it in their stride, but the men’s relentless hazing wore on the women Marines and many were furious. When the famous bandleader, Fred Waring, referred to the WRs as BAMs, a contingent got up and walked out during a performance at Camp Lejeune.

Marjorie Ann Curtner recalled a particularly mean-spirited stunt engineered by a group of Seabees who corralled every stray dog in the area, shaved them like poodles, painted “BAM” on their sides, and set them free to roam the ranks of a graduating WR platoon.

Crude language and blatant disdain took its toll on the morale of the Women’s Reserve and its director, causing the Commandant to take steps to end it. In August 1943, he took action and sent a clear message to the Corps, fixing responsibility for change on unit commanding officers.

However, things did not change overnight, but by mid-1944 open hostility gave way to some sort of quiet truce. It was not as much the Commandants ruling as it was the women’s dogged persistence, competence, sharp appearance, and self-assured pride that won over their heretofore detractors. A young corporal wounded at Guadalcanal put it into perspective saying, “Well I’ll tell you. I was kinda sore about it (the women Marines) at first. Then it began to make sense — though only if the girls are gonna be tops, understand.” Eventually, male Marines could even be counted on to thwart efforts of soldiers and sailors who dared to harass WRs in their presence.

Between 15 March 1943 and 15 September 1945, 22,199 women went to recruit training and of these, 21,597 graduated. The remaining 602 were separated for medical reasons or because they were found unable to adapt to military life.

Officer Training

Early on, all the women in the Officer Candidates’ Classes were Class VI(a) reservists recruited directly from civilian life without the advantage of enlisted experience. Consequently, for the first seven Officer Candidate Classes, the primary emphasis was on attitude adjustment, forming new habits, learning the Marine Corps “way,” and adopting a military perspective. Close order drill was used to instill discipline and teach the women to respond to orders with precision.

To fill the growing need for female officers, a significant change occurred in July 1943 when the commissioned status was opened to enlisted women. This move capitalized on their experience while building morale and esprit de corps. To be eligible, a Marine had to complete six months of service, be recommended by her commanding officer, and be selected by a board of male and female officers convened at Headquarters, Marine Corps. The eighth officer class, in October 1943, was made up of both Class VI(a) and Class VI(b) reservists — the latter being Women’s Reserve enlisted. Eventually, the majority of new women officers came from the ranks and only civilian women with critical, specialized skills or exceptional leadership qualities were accepted for Marine officer training.

Specialist Schools

From the very beginning, selected officers and enlisted women were given specialist training and by the end of the war, 9,641 women — 8,914 enlisted and 727 officers — attended schools run by civilians, the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps. By the end of the war, women attended some 30 specialist schools proving to themselves and the world what women can do: first sergeant, paymaster, signal, parachute rigger, aerographer, clerical, control tower operator, aerial gunnery instructor, celestial navigation, motion picture operator/technician, aircraft instruments technician, radio operator, radio material teletypewriter, post exchange, uniform shop, automotive mechanic, carburetor and ignition, aviation supply, and photography.

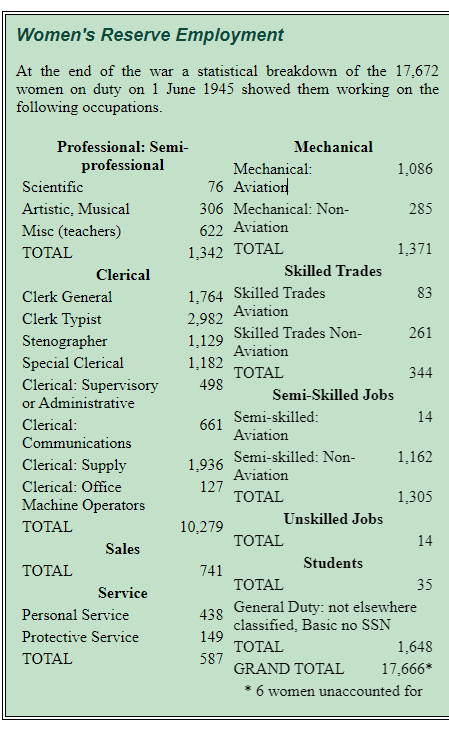

The most open-minded military units throughout the war and after were the aviation components of all the services. Perhaps because they were relative pioneers themselves, aviation leaders were less tradition-bound. They enthusiastically asked for large numbers of women and were willing to assign them to technical fields. Nearly 40 per cent of the Women Reservists were in the aviation field. Because of the large number of women posted to air commands, Twenty-one Aviation Women’s Reserve Squadrons were formed. The attached table shows the number of women Marines that served in these occupations.

NOTE: Much of the material for this article was extracted from “FREE A MARINE TO FIGHT: Women Marines in WWII” by Colonel Mary Stremlow and from “US Marine Women’s History 1943 – 1946”.