Bernice Trotter

USMCWR

By Tim Stanley Tulsa World

But as she stood there with her parents, watching his flag-draped casket being unloaded from the train, it felt almost like she was losing him all over again.

“Today the word we’d use is ‘surreal,’ ” Trotter said recently.

Describing the arrival of the remains of her brother, Franklin Pearson, back in Tulsa in 1949, she added, “Your first thought was that it just can’t be. It must be a mistake.”

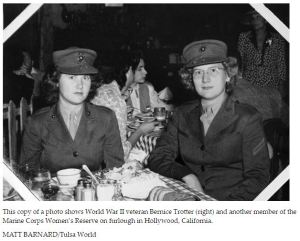

Trotter, like her brother, had served in World War II. In fact, they had enlisted within a few weeks of each other — she with the Marines, he with the Army.

But unlike her brother, Trotter lived to see the war’s end.

The news that he’d been killed in action in Germany, she said, shook the family.

Even though Trotter — like most servicewomen at the time — was stationed stateside, far from combat zones, a kind of guilt would gnaw at her for a long time afterward, she said.

“I kept asking myself, ‘Why did I come home and he didn’t?’ ”

Fighting her way in

Before he went

She brought it out during a recent interview with the Tulsa World.

In the picture, Franklin is dressed in his uniform, while Trotter, playfully, has donned his Army hat, which is too big and descends to conceal one of her eyes.

Arms around each other, sporting big grins, they couldn’t look happier.

“It’s the last one I have of him,” said Trotter, 92.

Neither she nor her brother — two years older and her only sibling — were required to join the service, she said.

But for different reasons, both felt compelled to volunteer.

Franklin, married by then and with a little girl, was exempt, working as a machinist at a factory producing war materials.

“He didn’t tell anyone he was going to enlist,” Trotter said. “Not his wife, any of us. He just came home one day and he had done it.”

They found out the “why” later.

“He said people kept asking him why he wasn’t in the service,” she said. “It got to him, I think.”

As for Trotter, like her brother a graduate of Rogers High School, it was a sense of duty. She had wanted to join earlier, in fact, and considered the Army Air Corps briefly after a friend tried to get her to join with her.

“But I thought the Marines were the best. And why not go with the best?” Trotter said, smiling.

In early 1943, however, when the Marines first began accepting women, she was too young — under 21 — to join on her own. And her parents wouldn’t give their consent.

“It felt like I was having to fight my way in,” Trotter said.

At last, in October 1944, word arrived that she was accepted.

But in some ways, the fight had just begun. Earning the respect of the men — “that was our battlefield,” Trotter said, adding that some of them resented the idea of women in the Marines.

“It was a generation where we believed it was a man’s world,” she said. “There was a stigma (about women doing men’s jobs). Women being in the military was unheard of — and yet it was a necessity.”

Breaking traditions

Trotter remembers well the day that signaled big changes — not only for women’s roles, but to every aspect of life — were on the way.

It was Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, and she and her family were at a cousin’s house in Tulsa after church when they heard about the Pearl Harbor attack.

“We all looked at each other and asked, ‘Where is Pearl Harbor?’ ” she recalled. “We had to get out a map and find it. No one, not even the adults, knew where it was.”

For one thing, she said, there was no family tradition of military service. The closest anyone had come was her dad during World War I; he “had his foot on the train to go,” she said, when the armistice was declared.

Beyond that, though, women weren’t even being accepted for service then. And it would be several months after Pearl Harbor before that changed.

The Marines, it turned out, would be the last branch to begin accepting women during the war.

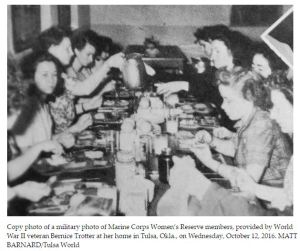

The Marine Corps Women’s Reserve was established in January 1943. Like the other military women’s programs at the time, the idea was for women to take over the clerical and other jobs of the male troops, allowing the men to be sent to the war.

‘Scared to death’

Completing trai

Soon after arriving, she learned that she would be driving a jeep for one of the majors.

The only problem was, Trotter said, she didn’t know how to drive.

“I never learned. My family had one car, and it was for business,” said Trotter, adding that as a schoolgirl she relied on “Lightning,” her blue bicycle, to get around.

“So I told the major ‘I can’t do this.’ I was scared to death,” she added. “But he just said ‘You’ll learn.’ I’ll never forget it.”

Assigned to “PFC Bernice Pearson, Camp Pendleton,” the vehicle operator’s permit she went on to earn holds a place of honor in her scrapbook.

“The major was right — I learned,” she said, smiling. “I was so proud of that (permit).”

Not quite as proud is Trotter of another aging slip of paper in her scrapbook. But as her first warning for speeding — she got pulled over running an errand in the major’s jeep — she thought it, too, worth hanging on to.

Feeling of power

She confesses she enjoyed the small feeling of power that came with it.

“Sometimes it was nice to say ‘no’ to certain people,” she said, smiling impishly. One of them, she added, was an officer who got livid once when she told him he wasn’t eligible for more tires.

He took her to her major to complain. But the major backed her up, she said, and it gave her a boost of confidence.

“He said ‘What did Private First Class Pearson say?’” she recalled. And that was the end of that.

Another of Trotter’s favorite memories of Camp Pendleton was seeing President Franklin Roosevelt when he visited the base.

“We were told to stand perfectly still,” Trotter said. “But I cocked my head to the side a little — so I could see him better” as his car passed by.

“He had his famous cigarette and holder. … It was just unimaginable for a kid that age to see your president.”

A brother’s support

Every now and then Trotter wondered what her brother was up to.

Growing up together in Tulsa, she and Franklin had been close, she said. “He was my idol. I always thought everything he could do I could do.”

They wrote each other after leaving for the service, and she still has three of his letters.

In one, he mentions learning of her enlistment.

“He said, ‘I’m glad you are in the Marines. You’ll do it proud,’ ” Trotter said.

The words still touch her after all these years. With most of the family, reaction to her enlisting had been less than enthusiastic. But here — from the brother she looked up to more than anyone — was validation, she said. It made her feel good.

Sadly, the words would be among Franklin’s last to her.

Trotter remembers well how she got the news one day in April 1945.

Called to report to the major’s office, she said, “I kind of suspicioned it was (bad news). Because it was not a normal thing to be called to the major’s office.”

Red Cross officials were there waiting for her. From them, Trotter learned that her brother had been killed.

Later, she found out the circumstances. Franklin, a private with the 63rd Infantry Division, had volunteered as a message runner. On April 8, while delivering a message, he was cut down by enemy fire.

Exactly one month later to the day, on May 8, news broke that Germany had surrendered.

“We all thought about that,” Trotter said. “Why couldn’t he have lasted one more month?”

Franklin was buried in France with other fallen American servicemen. Eventually the family arranged to have his remains returned to Tulsa.

Four years after his death, in 1949, the train arrived bearing the casket. “I remember my mother saying, ‘Oh, if I could just see and know that it was him in there,’ ” Trotter said. “We had his dog tags. But you couldn’t help having small doubts.”

Franklin was buried at Memorial Park Cemetery. Trotter still visits the site, which is next to her parents’ graves, often.

“Family life was never the same again. Not for my sister-in-law or niece. Not for any of us,” she said.

Franklin’s widow married again. Trotter stayed close with her and her daughter, she said.

‘I did what I came to do’

Trotter said she never knew the name of the man whose job she took.

“It still haunts me to this day,” she added, not knowing “if he came back or not.”

So many of them hadn’t.

The day the 4th Marine Division departed Camp Pendleton for the Pacific, where it would help invade Iwo Jima, is one she will never forget. Many of the women Marines, including friends of Trotter’s, had fiancés in the group.

“We would be there later when they got the notifications,” she said of those whose men were killed. “We tried to be supportive.”

Supporting her fellow women veterans is something Trotter has always been serious about. She’s a longtime member of the Oklahoma Women Veterans Organization and, just this past Saturday, enjoyed herself at the 32nd annual Oklahoma Women Veterans Recognition Day celebration in Tulsa.

She greatly admires and respects the women of later generations who served and believes they contributed much more than she did.

Even so, she said, when her service ended, she was satisfied. “I had done what I came to do. And being accepted as having served means a lot.”

After returning to Tulsa in 1946, Trotter married Ed Tr

otter, a Navy veteran, and together they raised three sons. They were married 50 years until his death.

Trotter has lived long enough to be well-acquainted with loss. She still thinks often of her brother, Franklin, and her parents.

But there’s one thing, Trotter said, “you can’t take away from me.”

“Once a Marine, always a Marine. I have never regretted that I served my country in the Marine Corps.”

Tim Stanley

918-581-8385

tim.stanley@tulsaworld.com